The following interview took place towards the end 2016. It was conducted by John Davidson, Professor Emeritus of the Classics Dept at Victoria University. John had seen all my production and adaptations of Classical works, and the precision of his questions attest both to the depth of his own reading and his deep concern for the transmission of the Classics.

Recently, the interview was published by the Open University with the title.Practitioners’ Voices in Classical Reception Studies, edited by Marguerite Johnson. Three practitioners were interviewed on their attitudes to the Classics and these interviewes can be found at http://www.open.ac.uk/arts/research/pvcrs/2017/australasian

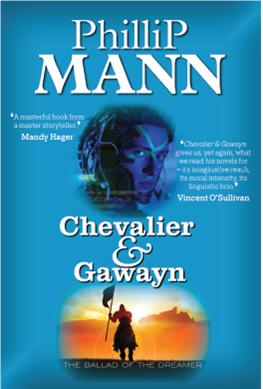

Phillip Mann was born in North Yorkshire, and studied Drama and English at Manchester University. He has worked extensively in Theatre in Europe and America and established the first programme of Drama Studies at Victoria University of Wellington in 1970, where he was later made Professor of Drama. Recently he has been appointed MNZM (Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit). He takes a special pleasure in directing new plays and in finding ways of making Greek Classical Drama available to modern audiences. In addition to his theatre work, Phillip Mann is a freelance writer and has published eleven Science Fiction novels as well as essays, plays and works for younger readers.

John Davidson was born in Lower Hutt and lives in Wellington. In 2010 he retired as Professor of Classics at Victoria University of Wellington where he was a colleague of Phillip Mann for many years.

This interview was recorded in Wellington on 21st October 2016.

John Davidson. I’m guessing that your interest in ancient Rome began with studying Latin at school. But how did you come to be so passionately involved with Greek tragedy and comedy?

Phillip Mann. My interest in the classics began long before I thought of them as classics, but certainly my interest was quickened and deepened by my study of Latin. My regret was, of course, that I never had the opportunity to study Greek – but more of that later.

My mother was an exceptional woman. As a girl she was very bright, could play the violin, loved dancing and was quite gifted as a painter. She loved learning and, more than almost anyone I know, she would have flourished and blossomed if she’d had the opportunity to go to university. This, incidentally, was one of the reasons why she pushed me so strongly to go to university and seek a career in the theatre. Unfortunately, when she was fourteen, my mother had to leave school to get a job. She was a victim, both of being a girl – not many girls went to university in those days, except perhaps the wealthy – and of the Great Depression. She had to work to earn money for the family. She was also a rebel, with a quick wit, and I am sure it was these qualities, plus a desire to break away from her family, that led her to get married to a man who was somewhat older than her, and who was, as far as I know, a South African serving in the Merchant Navy. This was 1942. It was a disastrous marriage, and the only thing she took away from it when the wretched man deserted her, was a baby boy, me. I was, and remained, an only child. She became, and remained, a solo mother.

I mention these things because from an early age I was the focus of her attention and, while she still went out to work, she lavished on me her own love of learning: of mythology, of the theatre, of spiritualism, of herbalism, of literature and of the arts in general. My earliest memories are of her telling me stories taken from Greek, Roman, Egyptian and even Māori mythology. She had always been an avid reader and, to the day she died, one never knew what books she would bring home from the library. My (humorous) theory was that she chose books at random, but, that wasn’t the case. She was simply a voracious and adventurous reader. To give but one example, when I was very young – I think it must have been about the time I was learning to read, though I can’t remember ever actually learning to read – she brought home a book of the plays of Aristophanes and read them to me. You can judge the antiquity of this book from the fact that the spicier and sexually explicit parts weren’t left in the original Greek but had been translated into Latin. True! She went to great lengths to work out what had been translated into Latin and later found a more unexpurgated edition. Of course, none of this meant much to me, though I did enjoy the comedy as she attempted to read the different characters. The one play I can still remember was Lysistrata. Thus, as I grew up I had a familiarity with names such as Socrates, Odysseus, Agamemnon, Plautus, Catullus and Sappho. I was also totally unaware that my mother was unconventional. As children, we tend to accept what is, as normal, be it poverty or wealth. But she planted the seeds of a love of learning, and it wasn’t until I was ten or eleven, that I realized how poor we were in financial terms, but how rich in other ways.

I had demonstrated a love of acting from a very early age. Then, when I was in my early teens, I was invited to play Pentheus in the Bacchae and that sharpened my understanding of that text. In the theatre, one learns by ‘doing.’ Among the Greeks, Euripides became my favourite dramatist closely followed by Aeschylus. And among the Latin writers, Plautus can still make me laugh.

JD. When you directed Greek tragedy, to what extent did you encounter misunderstanding and opposition?

PM. I think a lot of people are afraid of what are called ‘The Classics’ partly because they’re unfamiliar with them but also because there are some poor translations. Literal translations tend not to work, or else they become bogged down with footnotes, and so one has to find a better way of getting inside the text without oversimplifying it or perverting it. As a teacher, and this means as a theatre director also, my greatest joy has been when I’ve seen an actor suddenly become dramatically alive and discover the humanity and depth of the text. I remember directing the Trojan Women and seeing the actress playing Andromache weeping in the wings. It did not detract from her performance. She conquered her tears and her performance became all the more searing. The fact is, the classics need an open humanity, a willing sympathy, and an act of empathy, if they are to be understood. And, at the same time, one has to accept that there are some things that cannot be easily understood – in our world or the classical world – and which yet remain true to our human condition. Explain Auschwitz or Belsen or the casting adrift of refugee children in a leaking boat. Then consider the sexual passion and guilt of Phaedra, the blood-lust of Achilles and the totally destructive madness of Agave.

I have encountered misunderstanding and my enthusiasm has, at times, been treated as elitism. And that angers me because, first, it’s not true; second because ignorance is never bliss but usually a refusal to accept a challenge or an adventure of the mind; and third, because the truly great classical works address the most fundamental questions concerning our humanity. The more you examine your own fears, lusts, loves and passions, the closer you move towards the classical works, and especially the Greeks. We forget sometimes the frighteningly unstable and cruel world in which these works were born. “Call no man happy until dead.”

When I was directing the Bacchae at Downstage in Wellington, many years ago, I remember someone coming up to me and saying: “Well, if it was called the Front Eye, I might have come to it.” It is hard to make headway against that attitude. But, to be positive, I have found that the classics when directed simply and directly have always found a ready response from the audience. It’s because they tell the truth about the human condition. It was, I think, F. L. Lucas in his little book called simply Tragedy – and which I highly recommend – who said, “Tragedy is man’s answer to this universe that crushes him so piteously. Destiny scowls upon him: his answer is to sit down and paint her where she stands.”

JD. What gave you the idea of adapting Greek plays for a contemporary New Zealand context? Were you especially influenced by specific, previous literary creations exploring the interface between the classical past and the present in Australasia or the Northern Hemisphere?

PM. I can’t recall being influenced by any previous productions of classical works. My theatrical education has been extensive and, no doubt, my own work reflects the influence of my masters as well as my own experimentation. In this context, I should perhaps mention that, apart from the Greeks, my favourite dramatists are Brecht, Shakespeare and Molière, and I think their influence is evident in my work. In a way, Euripides is very Brechtian.

As regards the first part of the question “What gave me the idea,” I can’t recall ever thinking about the process. I do not consciously try to modernise, and the idea of dressing up Dionysus as (say) a foppish hippy would fill me with a kind of dread. That is not modernising, it is limiting. It’s reducing complexity and paradox to something that’s easy to understand. That is not what art is about. Modernising is a natural and unforced result of being open and available to what a play tells us. The more one seeks to understand and reveal these works, the more they become modern simply because we are of our own age. The greatest imperative is to be true to one’s own artistic sense … and to trust it.

In the case of the Persae and They Shall Not Grow Old, I wanted to see if I could understand the very earliest extant Greek play that we have. Aeschylus intrigues me and always has. I think of him as an experimental dramatist, forging a new kind of art. In this he is like Brecht. When I first read the Persae I knew I was in the presence of a man who knew exactly what he was talking about. I was moved by the fact that he could feel compassion for the enemy that he had helped kill. I felt the bigness of his work, and this was what I wanted to convey.

I already had a knowledge of the Gallipoli landing from working on Maurice Shadbolt’s Once on Chunuk Bair, and the parallels between the two events – the Persians attacking Greece and the British attacking the Turks – became evident. However, what finally unites them is the sense of loss, of waste and of destruction … And it was that which I tried to convey in the final images when the dead rise up.

I have a little dictum that I discovered early in my career as a director. It states, “Good ideas solve problems. Bad ideas create them.” Everything that happened in the production of They Shall Not Grow Old was a simple and logical extension of the first idea; that the events in the Persae mirror events in the modern era. The names change, the location changes, but the essential event, and the compassion that it generates, do not.

Which things said, I have to admit that I had a lot of fun with the Persae – the sound effects with wind-chimes and fans, the women dancing in their flowing robes, the magical exhumation of Darius, the long, staggering defeated walk of Xerxes at the end, and the concluding threnody – all of these stemmed from the initial vision of Aeschylus. It was one of the most enjoyable productions I have ever done, and I think this showed.

JD. You were something of a trailblazer in introducing Māori waiata into the choral element of Greek tragedy (something which others have subsequently picked up on). What similarities do you see between the lyric tradition of the Greeks and that of the Māori?

PM. I remember reading, in a book by Gilbert Murray I think, that the choric moves in Greek drama derived from battle tactics, and that idea has stayed with me from the first time I saw a haka performed. I have also been moved by the waiata tangi, the lament for the dead or dying. The Greeks, like the Māori, were a warrior nation.

The poet Alistair Te Ariki Campbell, who was himself a classical scholar and whom I knew quite well after directing one of his plays When the Bough Breaks, also mentioned to me the parallel after he had seen my production of the Bacchae. However, I didn’t have a deep knowledge of Māori culture. I’m cautious as regards cultural similarities – it can be very misleading.

JD. Apparent in your work, is a strong sense of the horror and futility of war, and the suffering of its victims, especially women. Did anything particular in your life give rise to this?

PM. I must confess I wasn’t aware of this. However, I think your question is very perceptive. I have some memories of WW2. I was born in 1942 and can remember a special kind of children’s gas mask that I hated because of the smell of the rubber. I can also remember being put in an iron shelter and being very afraid. My birthday is the 7th August and I can remember the shock in my small family when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th and then on Nagasaki on August 9th in 1945, which would have been around my third birthday. I felt that somehow I was to blame for something terrible – but I didn’t know what. These are residual memories.

After the war, I saw my mother and my grandmother skimp and save. I can’t remember that I ever lacked for anything, but as I grew up I came to realize how brilliantly these women – note there were no men – managed things: knitting, darning, repairing, gathering, cooking, saving. Life had the virtue of simplicity, but was never boring. There was relative equality too as all the families I knew had lost men in the war. I have written about this in a series of stories called Coming of Age in’t North. I created a fictional family.

Much later, when I went to Scarborough College (I’d won an open scholarship which paid the fees), I was a member of the Army Cadet Force for some years and was a specialist at map reading on the North Yorkshire Moors where we had mock battles. As an army cadet, I visited Belsen Concentration Camp and other wartime locations in Germany. I was 14 or 15. These visits left an indelible impression on my mind. I wrote a poem about it and even now, if I close my eyes, I can see the heaps of used shoes on display, and the several large tumulae erected over the bodies of those prisoners who had been murdered.

While I can’t pretend to be a pacifist – that requires a very special courage – I am very strongly on the side of peace and this is perhaps what gives my work in the theatre its edge. I directed Bent (by Martin Sherman) which deals with the persecution of homosexual prisoners in Nazi Germany and is set in Dachau, and I directed the first professional production of Shuriken (by Vincent O’Sullivan) which deals with the so-called ‘Featherstone massacre’ of Japanese prisoners. There are many other experiences too that have shaped my feelings. I have directed Once on Chunuk Bair, and am somewhat ambivalent about the way Gallipoli has been celebrated. While we can admire the courage of the men who fought and we can justly celebrate their bravery, we should rise up in rage against those who made it happen, and I don’t mean the Turks. I’m also thinking also of Vietnam, Afghanistan, The Falklands and Iraq.

When you look around you today … well the world has gone crazy. Who can make sense of it? There are now no easy solutions. Basically, I think that we, the people, have outgrown the politicians. We know what the world needs and it isn’t more guns or more slaughter. I’m ashamed of countries like England and the USA which trade in armaments. It has to stop! I would feel honoured if any of my work – whether in the theatre or as a teacher or as a writer – helped bring about peace and a deeper sense of common humanity – for that is what I write about. This is a very big topic. I didn’t set out to write about war and the pity of war, but there we are … Often one is not aware of the implications of one’s work until they are pointed out by a thoughtful critic. I don’t have an agenda, as such, in my books. I don’t have specific situations in mind. But, I do write from the heart.

Writing is extremely emotional, and not infrequently I have to stand up and walk away from the typewriter, computer, whatever … as the emotion is so great.

JD. Your Science Fiction tetralogy, A Land Fit for Heroes is a remarkable work. What was the impetus behind your reception of ancient Rome here, and can the presence of the ancient world be felt in any of your other SF novels? Also, do you see the failings of the Roman Empire as a metaphor for the failings of our contemporary world?

PM. The books grew from a short story, as have so many of my books. It just kept getting longer and longer, the characters became more complex, and the conflict between the intuitive Celts and the Ir-Rational Romans became sharper. I can’t explain it, but the four volumes just flowed from me. I did just enough research to know what I was doing, and I could remember just enough Latin. A conversation with your old friend (and mine) Alex Scobie helped immeasurably. The rest was pure invention, but remember that I knew the Yorkshire Moors very well indeed. I was also encouraged by my editor who put the book in the same class as The Once and Future King. Unfortunately, my editor died, Gollancz was sold to Houghton Mifflin and the books fell between the cracks. There are very few reviews. As a friend of mine, the playwright Mike Stott, commented at the time, “It looks as if your books got straight from the printer to the remainder stand.” And he was right. It’s very sad because I regard those four volumes as among my very best writing.

JD. In reviews of A Land Fit for Heroes, how much attention was actually paid to the Roman reception aspect as opposed to consideration of character, plot and so on?

PM. As I say, there were very few reviews of A Land Fit for Heroes. It was published and then vanished. The best (and only) review I have is of Stand Alone Stan by David Groves. He does me the honour of taking my work seriously. Perhaps, John, you could do a retrospective review of the whole tetralogy.

Although I went to great pains to give the book a firm grounding in Roman antiquity – I lived in York for a while which was a Roman capital and was surrounded by Roman relics – I don’t think many people took that aspect of the novels seriously. I suspect they thought it was a bit like Asterix (which is also well researched) and that could be misleading. Apart from David Groves, there has been no substantial critical reaction.

JD. Do you see other possibilities for the adaptation of the ancient world and its integration into contemporary literature and art?

PM. Yes, antiquity is an open quarry. And I think there’s always an interest in the Greeks, Romans and Egyptians, to name but three influential societies – if only because their societies are now so alien to us. But still we need their intelligence and the capacity of their art to dissect and face unflinchingly the reality of our Comédie Humaine. I have just finished reading The Mighty Dead: Why Homer Matters by Adam Nicolson. It’s a remarkable book and essential reading for anyone who wants to understand and feel the glorious power of this great literature.

But I do worry sometimes that we might be going out on a limb. What would happen if a solar flare were to take out the Internet? Unlike our distant ancestors and some of the peasant societies which still exist, we are in danger of being disenfranchised.

I do not look back to a golden age. Every age faces its problems. My worry is that we may not face ours soon enough. We are in danger of being too ‘civilized’, too ignorant and too poor. I have often thought that intelligence has two aspects. The first is the ability to see a problem before it overwhelms us. The second is to have the courage and awareness to overcome the problem. And here we arrive at the importance of the arts and books and plays and singing and games: because, in the very best sense of the word, they educate us and shape our awareness of what it means to be human. Aristotle talks of ‘pity and fear’ for he was talking about tragedy, to which I would add ‘laughter.’

Recently, I wrote a little poem. I would like to end with it because I think it says more clearly what I’m trying to say now. When I wrote it I was thinking of all the children who have died while trying to escape oppressive regimes. It is called For the Children of the World.

***

For the Children of the World

May the children of the world

Have the strength to stand apart

From the anger, fear and hate

That daily shake their parents’ heart.

*

May the children of the world

Feel that time is their best friend,

With time to play and time to feed,

And time to sleep at good day’s end.

*

May hunger not threaten.

May water not poison

Nor pestilence darken their night.

May hopes remain constant

Laughter stop sorrow.

May children be children

As is their right.

*

May the shouting of soldiers

Fade like an echo.

May the thunder of canon

Be a storm that is passing.

May the calm that sustains

All things, be apparent,

And our world of difference

Be a cause of delight.